Louis G. Gregory (1874-1951) rose from humble circumstances in Reconstruction-era South Carolina to national and international prominence as a teacher and administrator of the Baha’i Faith and a champion of interracial unity.

Early Life

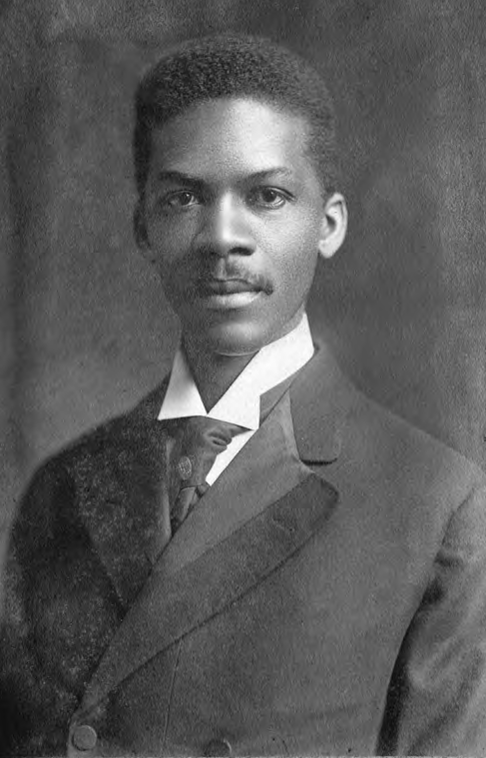

Louis G. Gregory as a young man, probably on graduating from Fisk University, 1896

Louis George Gregory was among the elite group of highly educated African Americans whom W.E.B. Du Bois called the “talented tenth.” He was born in Charleston in 1874, less than a decade after his parents were emancipated from slavery in rural Darlington County, South Carolina. Raised by his mother and his stepfather, a Union army veteran, he attended the best schools available to blacks of his day, including Charleston’s Avery Institute, Fisk University in Nashville, and finally the law school of Howard University in Washington, D.C.

As an attorney at the U.S. Treasury Department, Mr. Gregory became active in political and cultural life in the nation’s capital, including as president of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, one of the oldest African American cultural organizations in the city. In 1905 the Washington Bee, a local black newspaper with a national reach, lauded him as "one of the most gifted writers and speakers in this country."

“That pure soul has a heart like unto transparent water. He is like unto pure gold. That is why he is acceptable in any market and is current in every country.”

Baha’i Leadership

In 1909 Louis Gregory embraced the Baha’i Faith, convinced that its spiritual and social teachings represented both a renewal of the spirit of Christianity and a solution to the problems of the modern world. In 1910 he became the first person to introduce the Baha’i Faith in the Southeast—including his native Charleston. Over the next forty years he visited 46 states, parts of Canada, Haiti, the Middle East, and Europe, presenting the Baha'i teachings to gatherings large and small, meeting with leaders of thought, and encouraging Baha'i communities. In the US, he often had to endure the dangers and indignities of Jim Crow travel and separation from his wife, a white British Baha’i.

As a lecturer, author, and organizer, Louis Gregory ensured that the Baha’i Faith came to the attention of a considerable portion of the African American public—and of a number of progressive whites—in the first half of the twentieth century. Several well-known African Americans became Baha'is, including Robert Abbott, publisher of the Chicago Defender; Nina Gomer DuBois, first wife of the scholar-activist W.E.B. DuBois; John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie, world-renowned jazz trumpeter and composer; and Alain Locke, Howard University philosopher and "Dean of the Harlem Renaissance." Through the efforts of Louis Gregory and his associates, the Baha’i teachings would have an important leavening effect on the emerging movement for racial justice in America.

“This Most Great Reconstruction which the majestic Revelation of Baha’u’llah brings to view, is not black or white or yellow or brown or red, yet all of these. It is the power of divine outpourings and endless perfections for mankind.”

"Most Great Reconstruction"

In an era when the Jim Crow system severely restricted the social, economic, and political opportunities for African Americans, Louis Gregory was elected to a number of important leadership positions in an emerging American Baha'i community--by a membership that was mostly white. In 1911, only two years after embracing the faith, he was elected to fill a vacancy on the local Baha'i administrative body in Washington, D.C. The next year, he was elected to the forerunner of the faith's national body. He served in that capacity for a total of sixteen years until shortly before his death. When Louis G. Gregory passed away in 1951, Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Baha'i Faith, posthumously appointed him as a Hand of the Cause of God, one of a small number of special international deputies, in recognition of his lifetime of service.

As one of the faith's national leaders, Louis Gregory helped promote the establishment of new local Baha'i communities across the United States. During decades when African Americans and other marginalized groups were striving for full participation in the mainstream political process, the local administrative bodies that Baha'is were building became unique laboratories for interracial cooperation. With the fall of the Jim Crow system in the generation after Mr. Gregory's death, tens of thousands of people, mostly rural African Americans, became Baha'is in South Carolina and other Deep South states. In 1972, when the national Baha'i community opened an educational center in Georgetown County, South Carolina to train new Baha'is as teachers and administrators of the faith, it was named the Louis G. Gregory Baha'i Institute after the native son whose life's work had laid its foundations.

Members of the local Baha'i administrative board of Sumter, SC, 1973

Further Reading

Baha'i Encyclopedia Project, "Gregory, Louis George"

Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Unity in America

Janet Ruhe-Schoen, Champions of Oneness: Louis Gregory and His Shining Circle

Louis Venters, No Jim Crow Church: The Origins of South Carolina's Baha'i Community